Salmon and Bill 44

It’s well-known there’s a housing shortage in BC and that it’s impacting people and our communities. Bill 44 was passed in November 2022 by the BC Legislature in response to this shortage. The Bill requires municipalities to amend their zoning bylaws by June 30, 2024 to allow small-scale multi-unit housing on single dwelling lots. What this means is that landowners can build triplexes and fourplexes on single-dwelling lots without having to apply for a zoning amendment or holding public hearings. You can see how this streamlined process could add much-needed housing in a relatively short time.

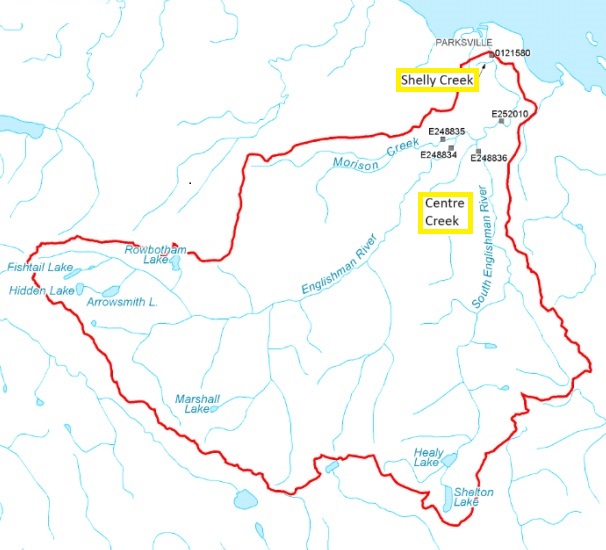

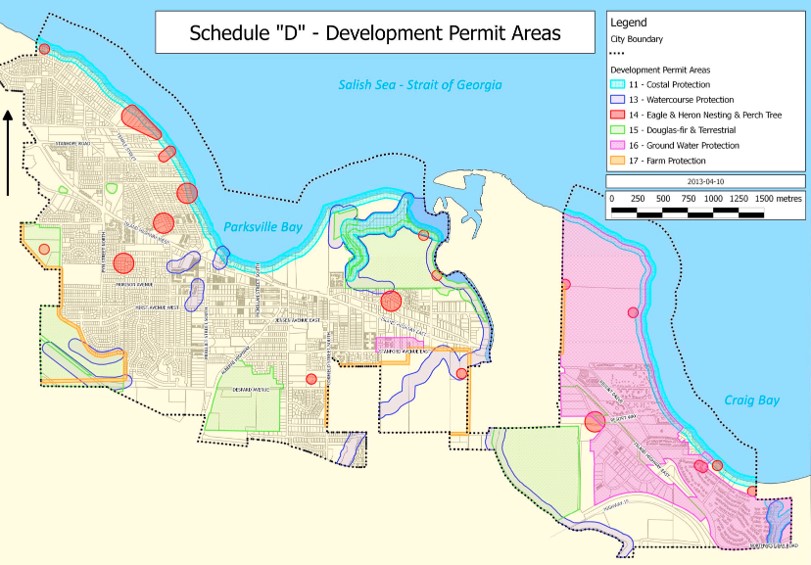

It also means that small-scale multi-unit housing could be built on the single-dwelling lots along the Englishman River and other sensitive ecological areas without a zoning amendment, and therefore, without the public hearings that zoning amendments require. That is, unless protective measures are already in place. Without public hearings, protection of Environmentally Sensitive Areas will depend on the Official Community Plan (OCP) and Bylaws. Parksville’s current OCP, written in 2013, contains Environmentally Sensitive Areas (ESAs) that are assigned Development Permits Areas (DPAs), shown in the map below. These DPAs contain conditions for protecting the environment during development. The OCP has seventeen DPAs with those for ESA's accounting for eight. For a definition of a DPA, and a list of the City's DPAs with their development regulations and guidelines, click on this link.

Since Bill 44 requires municipalities to update their OCPs with the amended zoning bylaws by December 2025, there will be an opportunity to ensure DPAs provide adequate environmental protection measures in response to the new zoning bylaw.

MVIHES made a presentation at the March 4 City of Parksville Council Meeting encouraging the City to start updating the ESAs and DPAs now so they are ready for the OCP update. Councillor Amit Gaur, also concerned with the implications of Bill 44, made a motion at the same meeting for single-dwelling lots in riparian areas to be a minimum of 4 ha in size and that development within the lots be low impact to protect rivers and creeks. The motion has been deferred until 2025 when the City will be working on the OCP. Both our presentation and Councillor Guar’s motion were highlighted in this PQB news article.

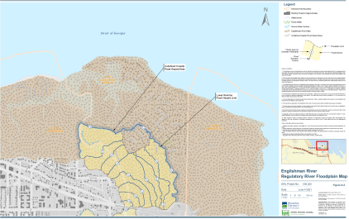

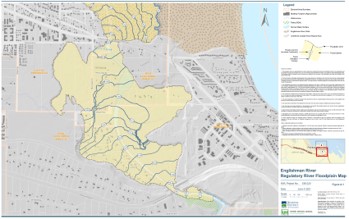

We would like to see the Englishman River floodplain (in the left-hand diagram) included as an ESA in the OCP. It's true that the Englishman River floodplain is already on a map in the OCP identifying Hazard Land Areas, and this imposes certain restrictions on development. But the DPA’s for Hazard Lands are written for the protection of property and human safety, not environmental protection.

Floodplains are essential for preventing serious erosion and destruction of fish habitat during extreme flood events, which will be coming more often with climate change. They provide a place for some of the roaring flood waters from rivers and creeks to escape, literally taking the pressure off the channels where fish and other wildlife live. If a floodplain is filled with buildings and roads, there is not enough space for all the water that would have filled that area so that water stays in the rivers and creeks causing serious damage to fish habitat....and possibly flooding of neighbourhoods.

Floodplains are essential for preventing serious erosion and destruction of fish habitat during extreme flood events, which will be coming more often with climate change. They provide a place for some of the roaring flood waters from rivers and creeks to escape, literally taking the pressure off the channels where fish and other wildlife live. If a floodplain is filled with buildings and roads, there is not enough space for all the water that would have filled that area so that water stays in the rivers and creeks causing serious damage to fish habitat....and possibly flooding of neighbourhoods.

Floodplains are also areas where floodwater is filtered and recharges groundwater. Some of that groundwater supplies flow to rivers and creeks in the summer, thereby maintaining streamflow during drought. If floodplains are filled with impervious surfaces like roofs, driveways, concrete patios and roads, this ecological function is disrupted.

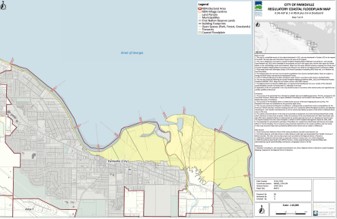

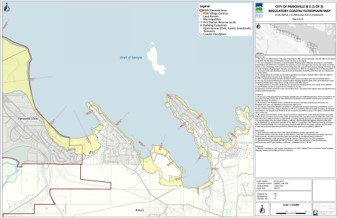

We also encourage the City to include the recent Coastal Floodplain produced for the Regional District of Nanaimo for sea level rise and storm surge (seen below) as an ESA, even though there is already a DPA for Coastal Protection. One of the environmental protection measures in the Coastal Protection DPA is the use of Green Shores methods for minimizing environmental impacts of shoreline development. With predicted sea level rise, the boundary in some sections of the current Coastal Protection DPA will need to be updated in OCP amendments as the shoreline moves inland. If the floodplain is an ESA for Coastal Protection, protective measures can follow the shoreline as it encroaches inland in a proactive manner and without having to draw a new boundary in an OCP update.

So why is using Green Shore methods so important? We have learned what hard armouring and retaining walls do to the intertidal zones of marine shoreline environments. Not only do they cause scouring away of sand that supports eelgrass, forage fish and other marine organisms, when sea level rises, they prevent sea water from moving up the shoreline to create new intertidal zones. This is called Coastal Squeeze. If the Coastal Floodplain were made an ESA, a DPA could ensure Green Shores methods continue to be applied as the shoreline moves inland and as new intertidal zones are created by sea level rise.

Fortunately, updating an OCP requires public consultation. The City announces when public consultations are coming up and we'll let you know as well. We encourage everyone who is concerned about the environment to participate in the OCP public consultation process when it happens. Your input could make a big difference. The salmon will thank you.

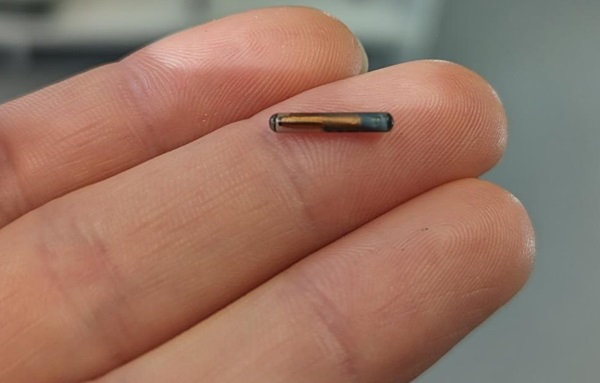

The ninth spawner was an adult that was tagged off Entrance Island (near Gabriola Island) in 2023 during the marine micro-trolling program. BCCF micro-trolls using miniature trolling gear (hooks, spoons, flashers) to capture juvenile fish for PIT tagging (right-hand photo). Except this wasn’t a juvenile. It was 21 inches long. And it had been clipped so it was a hatchery fish and therefore, not from the Englishman River. Thomas Negrin tagged that fish so we’re sure he’s thrilled to see it in Shelly Creek. You can watch a video on micro-trolling

The ninth spawner was an adult that was tagged off Entrance Island (near Gabriola Island) in 2023 during the marine micro-trolling program. BCCF micro-trolls using miniature trolling gear (hooks, spoons, flashers) to capture juvenile fish for PIT tagging (right-hand photo). Except this wasn’t a juvenile. It was 21 inches long. And it had been clipped so it was a hatchery fish and therefore, not from the Englishman River. Thomas Negrin tagged that fish so we’re sure he’s thrilled to see it in Shelly Creek. You can watch a video on micro-trolling